German numbers are weird because we kinda switch the last two digits.

43 in most languages becomes ‘40 - 3’, but in german you say ‘3 & 40’.

But we do not pronounce the whole number backwards.

143 in most languages becomes ‘100 - 40 - 3’, in german you say ‘100 - 3 & 40’.

I like the sense of suspense. Leave l leaves sometimes critical information to the last second!

The concept really is bullshit, and that’s coming from a German. For certain kinds of triple digit numbers people sometimes resort to saying the single digits in a row (“drei fünf neun” instead of dreiundertneunundfünfzig). Less misunderstandings, and faster.

dreiundertneunundfünfzig

And you’re trying to tell me that the german language is real?

That word isn’t real.

It’s spelled dreihundertneunundfünfzig

Look at this:

Dziewięćdziesiąt dziewięć

Listen to it in polish via web. I’m serious, listen to it.

Dziewięćdziesiąt dziewięć

Ḽ̵̩̠̣̤̋ő̷͙̩̟͎́͒͂̃ͅŏ̵͙̣̬ḱ̸̳̝̪̭̯s̶͔͂͗̀̕ ̴͉̊̈́̑̇f̴̝͖̖̳͆̅i̶̼͖̪̤̓͂̓̈́ń̶̩̎ͅe̸̗̥̣͛̈̍ ̴̙̈́̈ͅt̷̨̠̞̗͍̅̑̏̉o̴̻̝͍̿̏͑͆ ̶̱́̓̒̓͛ṃ̴̧̤͋̓̏̒̊é̵͎

Nein, ist sie nicht. Geh weiter, hier gibt’s nichts zu sehen.

I’ve been learning German and I call it the surprise ending language because everything is like that. In complex phrases, you often leave the primary verb until the very last word. So you might get something like:

I’d like to, with your daughter and a duck, this coming weekend, at the park, if it’s not raining, with our bicycles, go for a ride.

I will accede to your request but only under one condition which is that I come.

Ja, sehr gut! Ich liebe mit mein Freunden in dem Park Fahrrad fahren!

Just like dates in English!

*American

*honey

*English (Simplified)

- An American

wut? that’s language. Date order is American. There’s no such thing as English complex or simple or whatever for date orders. But there is British, if that helps you at all.

On things which have both British English and American English denoted by flag and name American English is often put as “English(simplified)” and British English as just “English”.

The order of dates has direct interplay with language syntax. January first, 1970 vs the first of January, 1970. It’s characteristic of the dialect of English and its spoken syntax, not just how dates are written.

If that’s the case, the German should write 143 as 134, since they pronounce it that way, yeah? /s

Over the border in the Netherlands we also do this and it annoys the crap out of me coming from another country.

In Belgium as well.

It even annoys me as a native, because it makes writing down a number someone else tells you irritating since it isn’t in the same order.

That is why I usually just give single digits when telling someone a phone number.

Huh. That’s exactly how we do it in Arabic.

I’ve always rationalized it as n + a set, so 43 is 3 and the 40 that we’ve added up before it.

But then we do the same thing you do with 100. 100 and 3 and 40. So we list everything from largest to smallest order of magnitude except for the last two digits.

I don’t think I’ve thought much about this since I was like ten years old (with a blip thinking about it in uni, when learning the different ways computers represent numbers). I remember getting tripped up with numbers as a kid when saying them in Arabic specifically because of this.

For another layer of headache keep in mind that we write from right to left but numbers are left to right just like in European languages. Funny.

Since I primarily use English despite being a native German speaker I always get those jumbled up and it bugs me so much. People dictate long numbers in sets of two or three digits, but instead of saying the digits, they say them as numbers. Then it’s like “3 & 40” and I write 34 because my brain goes “first number, first digit” until I notice that I made this error again and have to correct it. It takes way more mental effort than it should and it annoys me that so many people say these as numbers instead of as actual sets of digits, which wouldn’t be a problem in most other languages, but nooooo of course we need to add a good ol’ switcheroo right at the end there

okay, but the french multiply for 80…

Yes, I had to learn that too. It’s weirder for sure, but not in the context of this specific graph since ‘4 - 20 - [0-19]’ (80-99) still forms a neat cluster based on the first few letters.

That’s ridiculous

We only do that for the numbers 13-19, it’s much more logical.

I agree with the ridiculous. My kids were taught in primary school to write 123 as 1, 3 (with a blank after the 1) and the 2 (inside the blank). To this day I do not know if that is brilliant or stupid.

Also, we Germans do like our rules. If it works for 13-19, why change it 😎?

Up until not that long ago, this was the “correct” way of counting in Norwegian as well. Ein und zwanzig -> En og tjue. But tjue-en became more and more common, and nobody really cared that hard, so now this is more common. It’s still a bit of a mix of both depending who you talk to. Some, me included, use both.

Well wouldn’t you know it but this system got imposed on Slovenian through the Austrian states that ruled the lands through time. So now I think German and Slovenian are the 2 european languages that do this (disregarding all the other comments about norwegian, dutch and so on doing it both ways).

What about big numbers with millions and thousands and hundreds and tens and ones liiiiike 1,987,654?

‘1 - 1,000,000 - 900 - 7 & 80 - 1,000 - 600 - 4 & 50’

Large numbers are alway broken up into blocks of 3, pronounced like the initial numbers from 0 to 999 + the name of the long scale number (thousand, million, etc.).

Short scale, in english goes like this this: Thousand (3 zeros), Million (6), Billion (9), Trillion (12)…

Long scale, as used in german, goes like this: Tausend (3), Millionen (6), Milliarden (9), Billionen (12), Billiarden (15), Trillionen (18)…

Long scale kind of makes more sense since starting with Million the names just count upwards. Million, Bi-llion (2), Tri-llion (3), etc. But since you still start with Thousand in short scale, Billion is the 3rd, Trillion the 4th and so on. If you want to figure out Octodeci-llion (18), the formula to get the amount of zeroes in short scale is ‘18 * 3 +3’ and in long scale ‘18 * 6’. Also keeps the names pronouncable for longer than short scale. However, it does make translating the names of large numbers between both languages a nightmare.

One million nine hundred seven and eighty thousand six hundred four and fifty

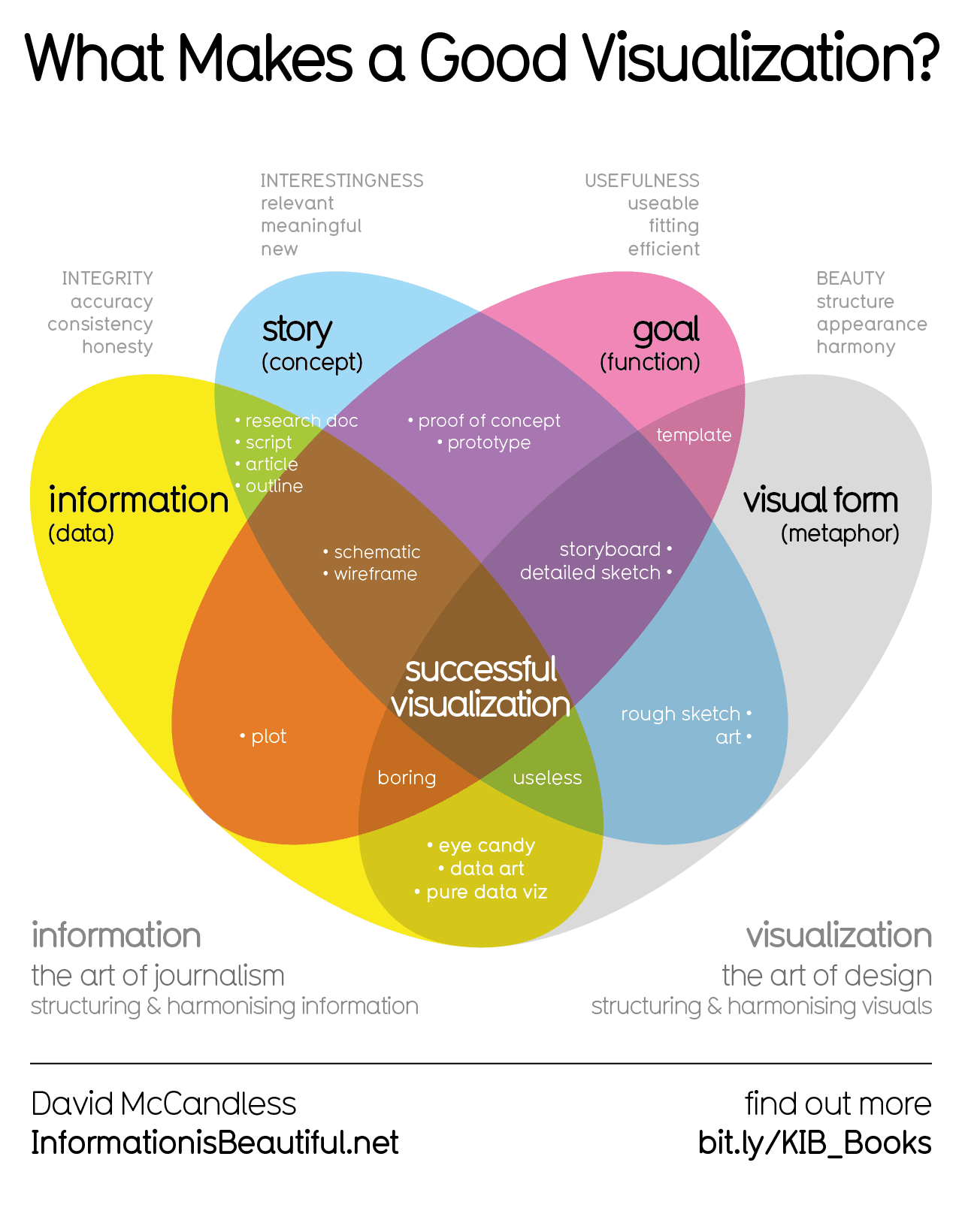

A bit confusing to read. The points are placed on the y-axis using ordinals rather than cardinals. This means if you were to extend the plotting (say, up to 200) it would cause the existing data points to move around. That’s not usually what we expect when plotting data.

Edit: actually, the problem is more severe than I initially thought. If the y-axis were plotted with cardinals (the way we usually plot data) then the German case would show 10 horizontal lines, immediately revealing a pattern in the data (caused by Germans speaking the ones digit before the tens digit).

Initially, I thought that you were talking about ordinal vs cardinal numbers (ie first vs one), which was a bit confusing. But, when trying to understand the placement of zwei in the German graph, I realized that you meant that the points on the Y-axis are sorted relative to one another rather than relative to the Y-axis scale as a constant.

I see that such plotting could be useful in some circumstances (shows some interesting clustering in other languages) but, I don’t like it.

What’s the problem? The y-axis is sorted from A at the bottom to Z at the top.

Let’s say you were plotting some temperature data. You take the temperature every day and record it for a month. When you go to plot the data, the normal thing to do is decide on the scale for the y-axis and then plot each temperature point according to where it fits on that scale. This allows you to see any trends in your data (perhaps it’s spring and the temperature is trending upwards over the month).

What you don’t do is sort your temperature data and then put the lowest temperature at the very bottom and the highest temperature at the top, with every other point spaced evenly between those extremes according to their rank. This completely obscures the relative temperature differences between the points!

Well this is what was done with the number words data we’re discussing. Look at the plot for English. Notice that zero is in the top left (because z is last in sequence), followed by one halfway up, which is also okay. But then look at two and three. You would expect two and three to be very close together because they both start with t, but they’re not. Words starting with t should be around 76% of the way up the y-axis (because t is the 20th letter of the alphabet) but two is at 99% of the way up and three is 77% of the way up.

This is problematic if you’re hoping to use the plots to spot trends. For example, with German (as another commenter pointed out) all 2-digit number words read the ones place before the tens place. If the data were plotted by cardinality (treating each word as a rational number between 0 and 1) then you’d easily spot this trend in German number words because all the points would fall on roughly horizontal lines.

Is there a good way to do this? I am thinking one could (taking English as an example) treat each word as a base-26 number (o.ne, t.wo, t.hree, …) and divide them by 26 to normalize values between 0 and 1.

Yes, that’s exactly the way to do it!

Oh now I finally see it. I thought all just gad their limits from A to Z, but they are all different. That’s just… wrong

All data points, from all series are sorted on the Y-axis relative to one another, not the external constant of the alphabet. This is contrary to how graphs are most frequently plotted and means that the shape of the data can change significantly, based upon the size of the dataset. It’s not that it’s an invalid way of plotting, just unusual and, personally, I don’t like it.

deleted by creator

Agreed. Proper graphs should be easily interpreted by most people looking at them, without asking a bunch of questions.

This one is a bit too out there. By a bit, much too far. This could not be published in a scientific journal. (Although a lot of published graphs aren’t great either).

Where is the german two (zwei)? Or am I reading the y-axis wrong?

“Zwei” is the one data point in the top left corner. The entire top row is 2,12,22,32 and so on, after 12 all these numbers start with “zwei” in German, and are therefore among the last 10 numbers alphabetically in this range. Happy coincidence that 12 just makes it into the last 10 digits alphabetically to not mess this up.

Thanks now I get it! I assumed only the first letter counts, so every number that starts with z should be on the same height

In position 91, behind 12 (zwölf) and all the decimal-2s (zwei-und-zwanzig etc)

deleted by creator

I feel like the graphs are misleading. Alphabetical position is really an ordered sequence which hides how visually apparent it would be if the left scale bar was first letter.

Am I reading this wrong? Why is “One” at the very top, signifying it is last alphabetically? There are many numbers that alphabetically come after that…

It’s not. It starts with zero.

But then “two” and “three” should be side by side no?

Edit: also “four” and “five”

It sorts the entire word. 4 is after 5 because FO is after FI.

Looks like pepperoni pizza slices

And the German ones look like oregano - sprinkled homogeneously.