It was 1984, and the publisher Macmillan was holding a small event for booksellers, and had invited a tiny handful of journalists along as well. They would be announcing upcoming titles, trying to get the booksellers excited about them. I was one of the journalists, but I only remember one author and one book from that afternoon. The author’s editor, James Hale, was thrilled about a first novel, which Macmillan would soon be publishing, and which James had discovered on the “slush pile” of unsolicited manuscripts. The author had been asked to say a few words to the assembled booksellers about himself and his book.

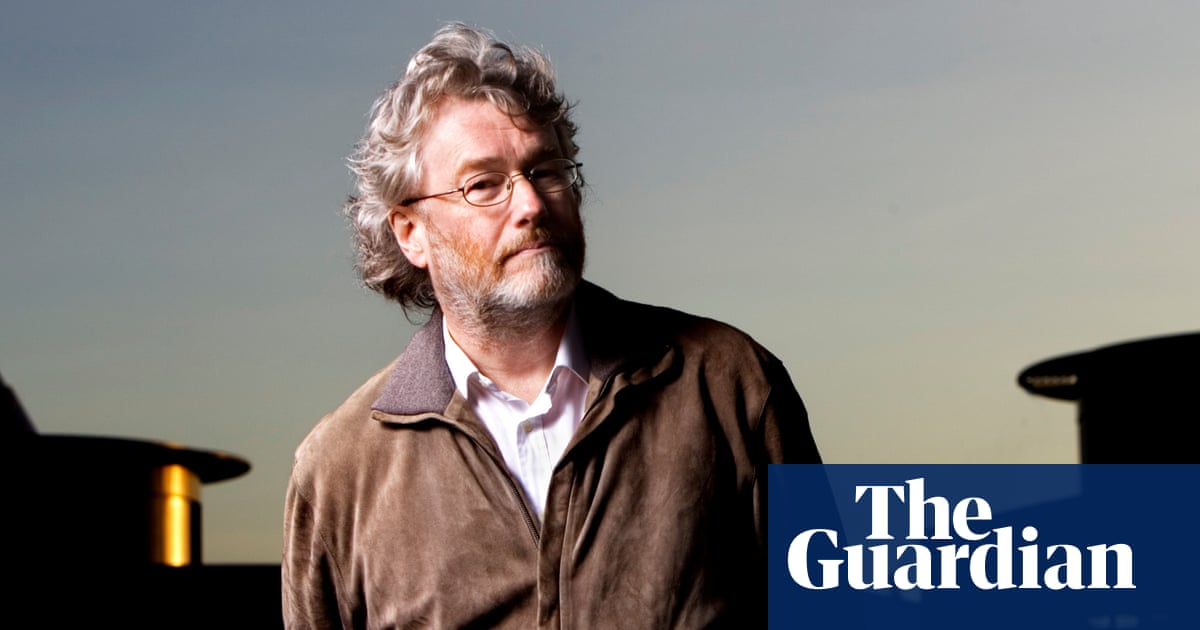

The author had dark, curly auburn hair and a ginger beard that was barely more than ambitious stubble. He was tall, and his accent was Scottish. He told us that he had really wanted to be a science fiction writer, that he had written several science fiction books and sent them out to publishers without attracting any interest. Then he had decided to “write what he knew”. He had taken his own obsessions as a young man, his delight in blowing things up and his fascination with homemade implements of destruction, and he had given them to Frank, a young man who also liked blowing things up but went much further than the author ever had. The author was Iain Banks, of course, and the book was The Wasp Factory.

The story, he told us, began when Frank’s brother, Eric, escaped from a high-security psychiatric hospital, and let Frank know he was coming home. But, Iain warned us, that wasn’t what the story was about. He told us that he didn’t like telling people what The Wasp Factory was about – but he would tell us. The Wasp Factory, said Iain Banks, with a straight face, was about 250 pages. The 100 booksellers and the half a dozen journalists were charmed and won over.

The book came out and immediately divided reviewers: some of us loved it while some seemed to feel that they had been personally attacked. Some saw it as an updated gothic romance, some as nothing more than a parade of nastiness, viciousness and monstrous things for their own sake.

In a stroke of PR brilliance, when the paperback came out, it carried quotes from both kinds of reviews on the cover, alternating those that heralded a remarkable new talent, that applauded the book for its imagination and its imagination and daring, with those that stopped just short of suggesting that the author should be locked up before he wrote another novel.

I read it, i think in 1987 and I was absolutely blown away by it. I had read “Consider Phlebas” before but this was something altogether different.

I was born in 1987 so I read it much later than that! I loved it but Consider Phlebas is more my kind of jam.